The first in a series – Random Date History. I love history, and (up to a point) the more detailed the better. I also love the feeling of discovering things randomly and accidentally. Therefore, I’m going to start posting here about random dates in history. To achieve this, I’m using the Random.org date generator, and – for the sake of having enough documentary evidence to use, while also not being too tediously current, I’m using a window of 1800-2000. I’m also going to focus on British history, but will bring in events from around the world when I feel like it. (After setting out on this course, I’ve only just realised that the format could have been influenced by the fact that I’m a bit of a Doctor Who fan, and this series could easily be called something like ‘travels in a temperamental TARDIS’.)

I’ve done my random date – proof here! – and we’ve landed. It’s Sunday 7th November 1802. What’s happening?

Politics

- William Pitt the Younger is not Prime Minister (as First Lord of the Treasury). Saying someone is not Prime Minister seems a bit of a non-event, but in this case it’s significant, because here in late 1802, Pitt resigned last March, having been PM since December 1783. Far from being a ‘mince pie administration‘ that would barely see out Christmas, he was in power for nearly 17 years. He was also only 24 when he took office, which is always quite amazing to think about. He could easily be characterised as the Mozart of British politics – a prodigy taught by his father, the Earl of Chatham, at home (the Earl himself had gone to Eton, and utterly detested it).

- But in November 1802, Pitt is out, having had a disagreement with the (famously ‘mad’) King George III about letting Catholics sit in Parliament – with the King vehemently opposed to even engaging with the idea. Pitt’s quite ill too – and having nearly died from some mysterious gastric complaint, he’s having a rest in this house in Bath. It seems that Pitt was an alcoholic, having been advised many years ago by a doctor to drink huge amounts of port. Here’s George Rose writing to the Bishop of Lincoln in November 1802 about Pitt in Bath:

“Mr Pitt’s Health mends every Day; it is really better than it has been ever since I knew him: I am quite sure this Place agrees with him entirely; he eats a small Duck & a half for Breakfast, & more at Dinner than I ever saw him at 1/2 past 4, no Luncheon; two very small Glasses of Madeira at Dinner, & less than a Pint of Port after Dinner; at Night nothing but a Bason of Arrow Root; he is positively in the best possible Train of Management for his Health: But in his way here, at Wilderness, he drank very nearly three Bottles of Port to his own Share at Dinner & Supper; so Lord Camden told me.” (my emphasis)

Extract from The Late Lord website

- Today, the Prime Minister is Henry Addington – far less well remembered than Pitt, and who Pitt thought was terrible at managing the nation’s finances. Addington, for his part, ends up trying to get Pitt back into office because there is trouble brewing in France that he just hasn’t got the skills or experience to cope with…

- Napoleon is in his ascendancy. He’s just been made First Consul for Life – a sort of Republican dictatorship – but in a few years will prefer the title Emperor, which will piss Beethoven off, as we shall see. Earlier this year, back in March, Britain and France signed the Treaty of Amiens. Britain had been at war with France for 10 years and Addington, being less hard-line than Pitt on Napoleon, went ahead with a rather doomed attempt at peace. (To me there are some parallels with the famous ‘Peace for our time‘ speech of Neville Chamberlain.)

- The peace of Amiens was followed by mass celebrations, and a programme of cultural exchange between Britain and France with “as many as 12,000 British subjects in Paris in September 1802” (link). One of them was Pitt’s great rival, Charles James Fox – and in November 1802, cartoonist Gillray characterised the meeting of Fox and Napoleon as ‘Introduction of Citizen Volpone & His Suite, at Paris‘, with Fox and his wife the large figures in the centre of the image below. In modern terms, Fox as the leading Whig is mocked as a sort of ‘woke’ Champagne socialist suck-up to the forces of revolution and democracy, as opposed to the monarchist, conservative Tories and Pitt (who called himself an ‘independent Whig’).

- This peace is doomed to be just an interlude between the Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars – and it seems there were preparations for war immediately after the so-called peace, followed by Britain declaring war on France in about six months from now – May 1803.

- Pitt does eventually return to power, in May 1804 – but dies in 1806 aged just 46. And if you’re not squeamish about death masks, here he is.

Culture

- 1802 is a pivotal year for Ludwig Van Beethoven. It is ‘the year when Beethoven became Beethoven‘ because he was turning from his early classical style to his middle-period ‘heroic’ style. As this Wikipedia entry says:

“Beethoven’s Second Symphony was mostly written during Beethoven’s stay at Heiligenstadt in 1802, at a time when his deafness was becoming more pronounced and he began to realize that it might be incurable”.

- However, despite this oncoming gloom, the Second Symphony is quite un-Beethoveny to most ears. A lot of the time it’s got a Mozart-like perky quality, with moments that remind me of the overture to the Marriage of Figaro. It’s good, but rather polite, not terrifically memorable – a Beethoven restrained by conventions and audibly struggling with them. However, Beethoven’s unleashed rage-gloom-defiance-joy is properly represented in the Third Symphony, which he started writing straight after the Second. The Third is a majestic rip-roaring piece of music and sounds almost like a different composer. And it was inspired, initially, by Napoleon – clearly in 1802 old Boney is in everyone’s minds. Beethoven originally titled the piece ‘Bonaparte’ in respectful tribute, but when Napoleon declared himself emperor in 1804, it was changed to ‘Eroica’. In November 1802 then, Beethoven is – presumably – still looking at Napoleon with admiration, and mentally brewing the amazing musical ideas that would create the genre of Romantic music. Check out the dissonant chord at 8:55 in the video below! I plan to turn this into my ringtone at some point.

- Romantic poetry is exestuating alongside the music. It’s now just over a month since the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge has his poem ‘Dejection: An Ode’ published – on 4 October 1802 in the Morning Post, which also happens to be his wedding anniversary, and his friend William Wordsworth‘s wedding day. Coleridge is married, but infatuated with another woman – Sara Hutchinson.

A grief without a pang, void, dark, and drear,

A stifled, drowsy, unimpassioned grief,

Which finds no natural outlet, no relief,

In word, or sigh, or tear […]

From Dejection: An Ode

- Coleridge is feeling ill as well as lovesick – he’s a highly emotional and sensitive character. (I’m a big Coleridge fan, in his over-the-top and irrepressible way he could be terribly self-indulgent, but in the next poem an absolute genius – exemplified by Kubla Khan, completed in 1797 and published in 1816). In two weeks from today, he will send this letter to his wife, from St Clears:

“I now write these few Lines in a hurry which yet, I trust, will be worth postage, because they will inform you that my Health continues to improve / & if I remain tranquil, I may return to you, a new Creation […] give my Love to Mary — & be sure to tell her & Mrs Wilson not to let Derwent & Hartley have any Tea. Milk & water equally hot — & they won’t know the difference. A weak Ginger Tea would certainly be useful to Hartley’s Bowels.”

Everyday life

- How would you, this cold Sunday, be feeling about the prospect of war? In November 1802 you might be blissfully unaware of the looming war, having thought that the peace of Amiens would hold and looking forward to your first war-free Christmas for a decade. Or you might be aware that trouble was around the corner and be thinking that we’d have to get Pitt back for some reliable leadership, health problems notwithstanding. These feelings would possibly depend on whether or not you read the newspapers. For instance, if you’d picked up the Morning Post yesterday, Saturday 6th November, you might be reading these words as part of a piece that focuses on a visit to Britain of Antoine-François Andréossy:

- … All very uncertain. The Treaty of Amiens is in fact a ‘preliminary peace’. We are definitely psyching ourselves up for the possibility of war. Perhaps we’ve thought about this, or even prayed about it, at church this morning.

- You might have tried to distract yourself from these concerns. If you were a Londoner, you could have seen actor-manager Stephen Kemble, ‘famous for playing Falstaff’, in The Merry Wives of Windsor at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane – “positively his last performance” in London (another newspaper reveals that he was asked to extend his run, but he had to dash off to Bristol).

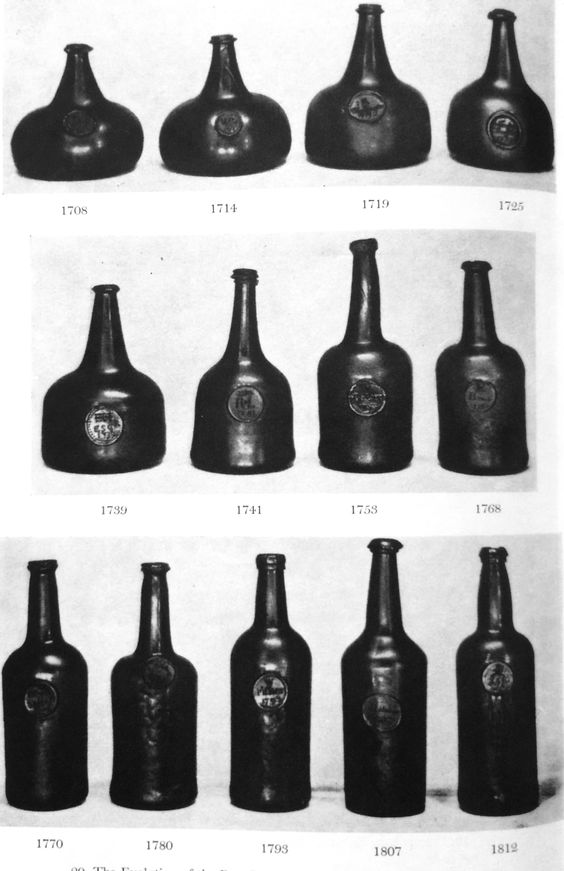

- It’s possible that if you’re a man, and you had gone out to the theatre last night, you’d have decided to abandon your powdered wig for the first time. William Pitt had introduced 17 new taxes while in office, including a costly licence to use hair powder that became an assessed tax in 1802. The era of men wearing powdered wigs (or on their real hair) was coming to an end.

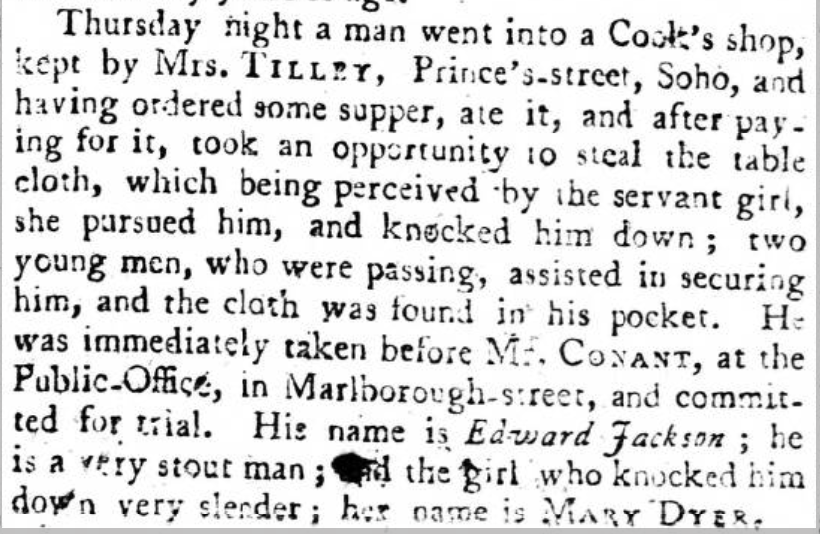

- You might also have scoured the back pages of court news to see this story about a ‘very stout’ man who tried to steal a tablecloth, but was apprehended by the ‘very slender’ servant girl, Mary Dyer.

- You might have forgotten where Prince’s Street is, and dug out your Wallis’ Plan. Ah yes, here it is:

- (…and here it is now.) We could perhaps go for a walk there – fortunately it shouldn’t be too wet …yes I checked the historical weather records for November 1802, and it was a below average November in terms of rainfall.

- On the other hand perhaps, like Pitt, you’re feeling a bit afflicted with gout and would rather not risk it – and wondering if some remedy advertised in the paper might alleviate your health problems, like W. Cole who had ‘wished those around me would put an end to my existence’ until he was sorted right out by ESSENCE OF MUSTARD. A lesson for us all, there.

At the end of the day

Sunday 7th November 1802 – it feels like a suspended, grey sort of day – waiting for winter to kick in, waiting for war to start, waiting for Pitt to return to government, waiting for Beethoven to break free of the classical tradition and create a new genre of Romantic orchestral music. And, of course, it’s Sunday. I bet that, even if it’s not raining, it’s drizzly.

Time to open another bottle of port.

Leave a Reply